Lolo Marciano, my grandfather, was unknown to me. He died when I was barely able to walk or speak. As far as my expanded family of parents, grandparents, grandaunts, granduncles, and far-away cousins were concerned, he was just another name tossed around after his demise. But lovingly and with much reverence.

I was a child when he passed, not having reached the Age of Reason, so I wasn't privy to all their secrets and intrigues, their mysteries and celebrations. They exchanged tales of far-flung rice villages with amorous adventures among village neighbors amidst fragrant rice fields, like magic realism. They spoke about lazy afternoons when young, able-bodied men with bronze skin, went courting and wooing the beautiful barrio maidens after arduous work in the rice fields.

Tales of bygone years spoke of longevity and wealth, enabled by the confluence of topography and natural resources. The Angat River irrigated the province’s flat terrain. It fed the sandy loam soil of its fields. Mango orchards flourished alongside santol and caimito trees. Backyard corn and vegetable gardens fed happy chickens and fattened pigs in Lolo Marciano’s expansive ancestral home.

My grandfather was born in the village of Longos in Bulacan province, known for the cotton trees that lined its streets. The Tagalog root word “bulak” meaning cotton gave the province its prodigious history.

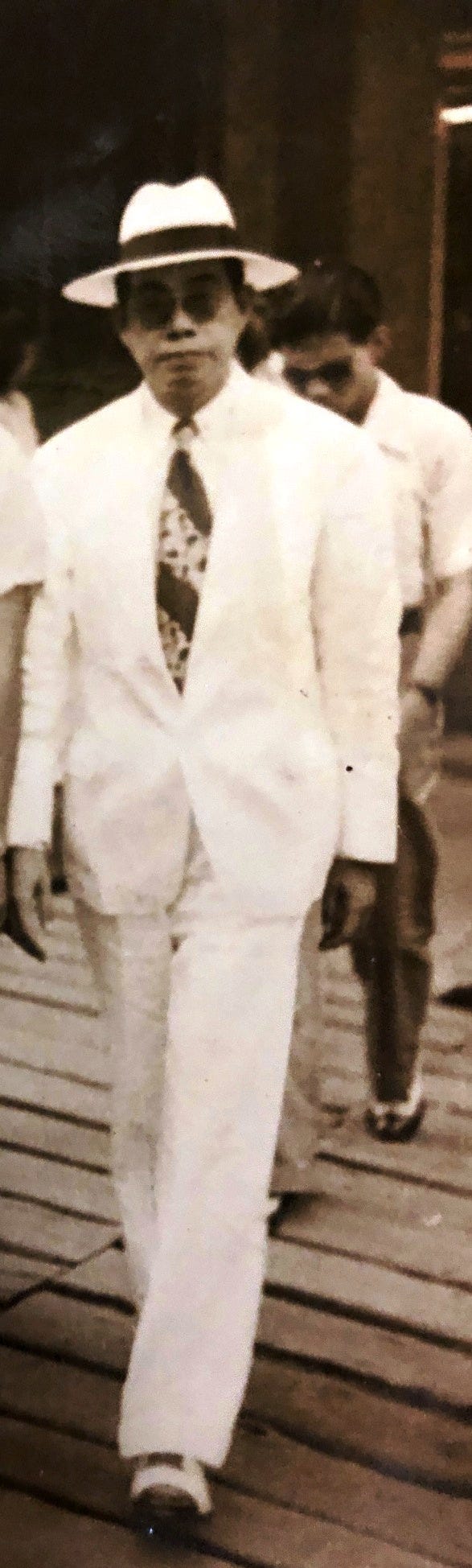

I heard stories about Lolo Marciano that were lofty and high-minded, like verbal obeisance for the reverence he possessed. He was a tall man, bespectacled, lean, without flab. A photograph shows him dressed immaculately in a white suit and a top hat, every bit a stately, commanding presence. He oozed machismo like Clark Gable and Jimmy Stewart, the heartthrobs of his generation. I thought of the many hearts that fluttered under his gaze. He sounded like a giant.

His short life of fewer than six decades was eventful. He was among the first in his generation to be educated in the American tradition. He put his education as a certified accountant in the service of rehabilitating the country devastated by war. He served as Comptroller of the Philippine National Railroad, the Manila Hotel, and the Pines Hotel in Baguio City in the immediate years after World War II.

Thus, I understood why my father chose to become a civil engineer. Following in my grandfather’s footsteps, my father worked at the Philippine National Railroad after graduation. Theirs is a story of family history, uninterrupted.

But it was a memorial school bearing his name, Marciano del Rosario Memorial School in the adjacent province of Nueva Ecija, that sparked my attention. The school stands on four acres of land donated by my grandfather whose agricultural lands spanned two provinces. Indeed, he was a man of means. And veritably, a man of generosity. The school stands proudly some eighty years later, enduring the passage of time, the onslaught of calamities, disasters, and the understandable fickleness and transience of humans.

For over eight decades, the school has steadily expanded and flourished, though it remains a simple two-story structure of wooden desks and chalk blackboards. Outside the school is a small, meticulously swept parking lot. A school van painted in sunshine orange is surrounded by a few tricycles, the hallmark of provincial mobility. The school’s low walls are a soft ecru color, the roof a cheerful lime green. In the morning sun, the grounds are speckless and sparkling. There is no Harvard courtyard or Stanford quadrangle. No heavy wooden banisters and walnut-colored wall panels of Europe’s well-endowed universities. But the archway entrance is a trellis of delicate white flowers under which the students pass through with utmost grace.

On YouTube, three high school female students talk proudly about the progress of their school, today equipped with a computer lab and a better-endowed library. A schoolteacher spoke of continuous modernization through technological innovation that would better prepare the students for a digital future. “Makipagsapalaran sa mundo,” (“to venture out into the world”) she said. The YouTube female trio spoke about their education at my grandfather’s school which nourished their personal growth. The school provided a rite of passage into an enlightened phase of their lives. It transformed them into productive members of society. They knew what education would give them: a gift to themselves. In turn, they would give back to society. Their conviction was, to say the least, humbling.

After much pondering a century’s worth of family history, I finally understood the long continuous arc of my paternal history through Lolo Marciano. His eldest daughter, Carmen, was herself an educator. She was Dean of the Philippine Normal College, having earned a Master's Degree in Education as a Colombo scholar at Yale University. His second daughter, Isabel, was a physicist who worked as a research scientist for a Philippine government agency. And I, an educator by profession, saw that uninterrupted line of commitment to education through my ancestors. I shudder at the thought of how human life is never random. Lolo Marciano’s life was short, sweet, and packed a punch.

My grandfather's story electrified Ria my niece in far-away Seattle. She claimed her heritage as the proud great-granddaughter of a visionary and philanthropist. She wrote on her LinkedIn page “one man’s dream of a better life through education.” Lolo Marciano’s singular act cemented his memory across time and space, across generations.

I have not met him in this mortal life. But I know him from our connection through memory and a few surviving photographs. Best of all, at the Marciano del Rosario National Memorial School entrance is a plaque standing on a tall concrete pillar bearing his name, his photograph, and the immortal words of Einstein: "Only a life of service is worth living."

But there is something to look forward to Another realm, where we are not bound by time, where physicality disappears and reality is the fullness of thought, all-encompassing, beyond our human comprehension. Or perhaps as a reincarnated being, following the mysterious Buddhist cycles of rebirth. Or as pure energy, vibrating in a boundless Universe. Finally, I hope to meet Lolo Marciano.

Hello Teresita, I am Nieves C. Villamin, a Cabanatuan native now living in Hilo, Hawaii. I am writing a book about Cabanatuan City and your Lolo is a part of it because of his generous land donations in Nueva Ecija where once upon a time was one of the provinces he served. I want to use his picture here, with your permission. Also for human interests, can I ask your permission to use some of your family's stories for my book? Thanks.