Jaime FlorCruz: Our Man in Beijing

China watchers, analysts, and commentators these days come out of the woodwork. Sinology has become a proper sub-field in East Asian studies. Universities aspiring for any measure of intellectual respectability host a China studies program. Their graduates produce a global army of Sinologists.

But Jaime FlorCruz is a league unto himself. He doesn't crawl out of the impenetrable Chinese tapestry to emerge as another China watcher. Nor does he go media-hopping to dabble in lofty abstractions as a glib scholar with packaged one-liner retorts.

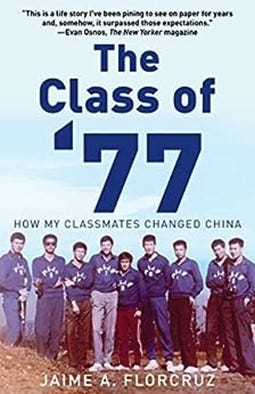

Instead, he wrote a book. Not so much about himself but about his classmates, those with whom he entered Peking University in August 1977. The book is called The Class of '77, aptly subtitled How My Classmates Changed China.

The year 1977 is significant. FlorCruz wrote that it was a "cathartic year of change, a year that began to percolate with pent-up energy and unfulfilled ambitions." Mao Tse Tung, the Great Helmsman, passed away a year earlier at 84 years old. Mao's most hated adversary, Deng Xiaoping, was rehabilitated as Vice Premier after being purged during the Cultural Revolution. Deng's political comeback would usher in a period of reforms that would "rescue China from the near-death experience of the Cultural Revolution to decades of growth that have astonished the world."

His classmates were would-luminaries of China's grand modernization program. The most prominent of them were: Li Keqiang who became China's premier, the second most powerful person in China; Bo Xilai, his history classmate, the charismatic leader of Chongqing province who oversaw the economic development success of the province and was imprisoned in 2012 for corruption and abuse of power; nuclear physics whiz kid Wang Juntao, co-founder of the Beijing Social and Economic Research Institute, China's first independent think tank, and a "democracy evangelist" who was imprisoned as a dissident and eventually exiled to the United States. Their stories are intertwined, "bound up in the saga of the university, (taking) part in China's renewed quest to modernize."

The transformation of China from what FlorCruz called a "Maoist dystopia" to an economic superpower is the metastory of this book. This overarching narrative could only be told through the lens of what sociologists call the “modernizing elite.” FlorCruz identified them as the class of '77. He recorded their stories and the swirling events of China’s dizzying transformation through his direct interaction with them.

But the book is also about FlorCruz himself.

The opening pages provide details of his "accidental" long sojourn in China when in 1971, he joined a three-week study tour arranged by the China Friendship Association as part of a 15-person Philippine Youth Delegation. He was a student activist then, eager to learn about the supposedly egalitarian society and the socialist utopia that was China's aspiration. There were no relations between China and the Philippines at the time.

Only the curious twists of fate can explain how FlorCruz's three weeks turned into twelve years in China. A bombing incident in Manila during their China visit put FlorCruz on the blacklist. He could not return home. He would have faced arrest upon his return along with four other delegation members. In a matter of three weeks, FlorCruz went from accidental tourist to unwitting refugee. He was just twenty years old. A year later, FlorCruz became stateless when his passport expired and there was no Philippine Embassy at the time to issue him a new one.

Like lucid ethnography, FlorCruz took the reader to Xiangjiang State Farm in Hunan province, where he and his fellow stateless friends lived and worked while stranded in China. Dressed in cotton-padded pants and jackets to ward off the cold, using communal latrines while watching white maggots crawl on the walls, and balancing a bamboo pole hooked on both ends with wooden buckets full of human waste to fertilize vegetable plots is the stuff of any aspiring anthropologist's field notes, notwithstanding their cringe-worthy value.

After over a year on the communal farm, he and his companions were reassigned to work for a fishing corporation in Yantai, Shandong province, for more manual labor at sea. They pulled fishing nets, shoveled fish into refrigerated containers, and learned Mandarin while battling homesickness, boredom, loneliness, desolation, and uncertainty that hung over their fate. Another two years in a socialist dystopia, the aquatic version.

But it was not all about back-breaking work and sociological ennui. There were escapades too. FlorCruz had his fair share of amorous dalliances. Smooching in an apple commune at midnight made me laugh. Getting caught by the local militia was terrifying. Their sudden separation was heartbreaking. Here was, after all, a young Filipino male at the height of what I can only imagine as a raging sexual appetite that no ideological programming could dampen. Seeing her again in an elevator at Beijing's Xinqiao Hotel three years later was poignant and emotionally wrenching as the elevator stopped at every floor so they could do a postmortem of the night under the apple tree. By then she was married to a Japanese businessman. She stepped out of the elevator on the 9th floor and he never saw her again. It was gut-wrenching drama, the stuff of unrequited love stories. Affairs of the heart do happen among involuntary exiles too.

"Thick description," as the venerable anthropologist Clifford Geertz called it, is an approach to field research that brought a refreshingly new perspective to the ethnographic method. Flor Cruz was trained as a historian, but his book could very well be used as an exemplary text for Clifford Geertz's anthropological vision.

The book is not just about amassing copious amounts of detail and local color, as anthropologists are trained to do. More importantly, ethnography is to observe and record social behavior within a particular context, to recognize deeper layers of meaning rather than just registering surface-level phenomena and to provide the webs of social relationships that connect persons to one another. In FlorCruz's book, the details of daily life were written in a larger historical context during the late stages of the Cultural Revolution, a cataclysmic period in Chinese history. But he does so against a backdrop of first-person immersion from the vantage points of the farm and the ocean, the bus and the train, the cramped cabins of the trawling boats, the city pavements, the rural mud trails, and the forbidding waters of the Yellow Sea.

He also wrote about people who touched his life: Teacher Song who taught him Mandarin and a few Chinese songs from revolutionary operas; Hai Ou who plucked the strings of his young foolish heart; Cai Housheng, the stocky staff officer at the Foreign Students Office who welcomed him to Peking University; Ana Segovia who ended his solitary bachelor days and co-created a solid family life in Beijing. These vignettes of literary ethnography are the author's gift of magnificent prose, an outstanding testimony to thick description.

As he navigated his readers into the transition period in the aftermath of Mao's death, FlorCruz described the winds of change that blew hard and strong. His writing has a frenetic quality, and the reader is swept in the euphoria of the transformation process that gripped the entire country. Universities reopened, students were excited to sit in competitive examinations (gaokao) to re-enter, once again, the hallowed halls of learning that were closed for many years during the Cultural Revolution. The collective hunger and the yearning for new beginnings were palpable.

Having mastered Mandarin, FlorCruz sat for the entrance exams and competed for a university education. In October 1977, he entered the West Gate of Peking University as a freshman in the middle of a gentle autumn season with chirping cicadas and croaking frogs as a fitting backdrop to his first day as the only Filipino student in China that year. He was elated at being accepted into the "Harvard of China," where he enrolled as a student of Chinese history.

This phase of FlorCruz’s life would be a watershed. He lived in the spartan dorm rooms, ate in the university cafeteria, and rubbed elbows with his Chinese classmates, several of whom would be catapulted into positions of power. It did not take long before American media giants would identify FlorCruz as their interlocutor. He went on to become a journalist for Time Magazine and CNN. As a Time magazine correspondent in Beijing, he broke the story of the suicide of Jiang Qing in 1991. She was Mao's widow and leader of the Gang of Four, who stood trial for treason shortly after Mao's death. Later on, he became the Beijing bureau chief for CNN until his retirement in 2014. By then, he was the longest-serving foreign journalist in China, a sterling achievement in and of itself.

On my first visit to Beijing in the winter of 1988, I felt the buzz. The city pavements bore the weight of an army of rural migrants to work as laborers in the construction sites and the factories. They traveled in buses, populated train stations, all of them on the forward march to rebuild a society that lay dormant for much too long. They were the backbone of China’s growth engine.

The newly-built Shangrila Hotel, the second five-star hotel at that time, was still relatively empty. But smartly-dressed Chinese women wore Western blazers, starched linen blouses tucked into short skirts. They wore stylish pump shoes with comfortable heels, deftly balancing food trays of steamed rice and Hainanese chicken. The monochromatic green Mao jackets, baggy trousers, and kung fu slip-ons were fading. Mao’s large footprint in Chinese society was slowly being reduced. That brief experience stoked my imagination of what life might have been before the hotels and the stylishly-dressed women arrived at the scene. FlorCruz’s book gave me the stories to imagine a bygone life.

The story doesn’t end here, however. In late 2022, FlorCruz was appointed Philippine Ambassador to China. One could read a thick ironic twist in this latest morphing of his life. Stranded in China for about 12 years due to former president Ferdinand Marcos’ blacklisting of FlorCruz, his life took another curious turn when Marcos’s son, now President Ferdinand “BongBong” Marcos, Jr. appointed him.

Or one could view this as full circle. He began his public service career as a student activist, youthful and brimming with energy to change the world. Today he is a top-notch diplomat in one of the most complex and sensitive foreign assignments anywhere in the world. Perhaps the unintended exile was a long preparation for this penultimate stage in his career. A new story waiting to be told, and written.

Now that would be a fitting sequel.